How do openings pull us in?

As I sketched out what I wanted to do in these Novel Studies posts, I started with a series of questions I wanted to answer, among them:

What makes this book/scene/character work?

What are the components the author is using (dialogue, action, summary, backstory, interiority, etc.), and how are they being deployed on the page?

What makes us want to keep reading?

I expect to add to and fine-tune this set of questions as we go along, but this is my starting list.

Let’s start by zeroing in on that last question: What makes us want to keep reading? In particular, how does the opening pull us into the world of the novel? What do we know? What’s implied? What’s left as a mystery?

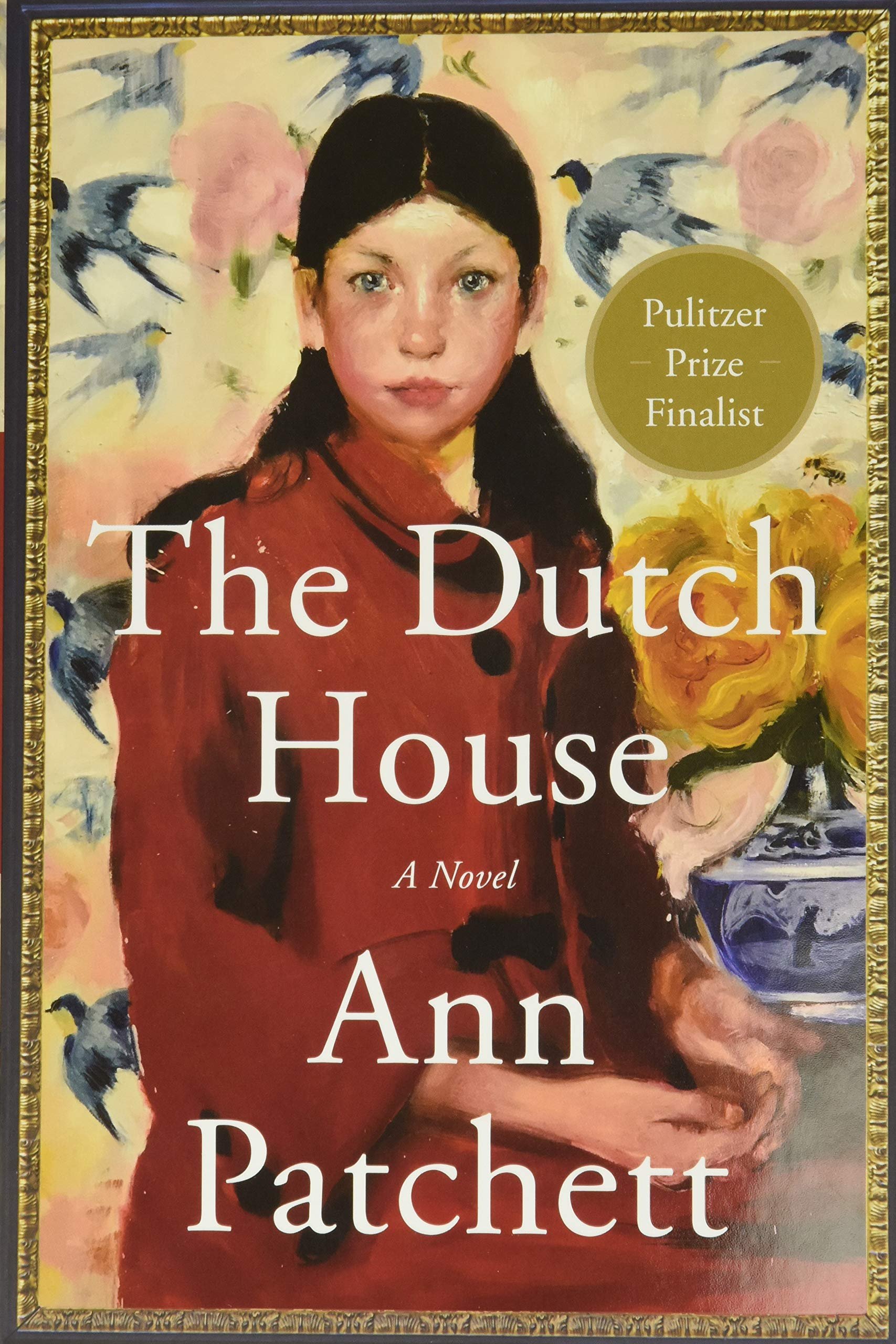

As we take these questions to our first Novel Study book, The Dutch House by Ann Patchett, let’s start with what the cover and title tell us, for they are indeed part of the meaning of the book. (One of my few quibbles about reading books on Kindle is that you are automatically taken to the first chapter rather than to the cover. Even if I’m viewing it in black and white on my Kindle Paperwhite, I want to see what messages the cover has for me.)

The cover of The Dutch House is a painting, complete with gilt frame, of a girl wearing a red dress with belled sleeves. Her gaze is level and direct, her facial expression serious. Her hands are open in her lap, partially cradling one another, as if she is holding something precious though her hands appear to be empty—an unusual pose. The background, with its patterned wallpaper and vase of fresh flowers at her elbow, implies wealth. Is this a room in the Dutch House of the title? And what is the Dutch House, anyway?

The first paragraph of the novel gives us another clue, but also raises more questions:

The first time our father brought Andrea to the Dutch House, Sandy, our housekeeper, came to my sister’s room and told us to come downstairs. “Your father has a friend he wants you to meet,” she said.

In addition to having a name, the Dutch House has a housekeeper, confirming the impression of wealth. What do we learn about the cast of characters from these lines? We understand intuitively that we are with an older narrator who is inhabiting a younger self. This narrator knows that the “friend” is named Andrea and that this is not the last time she’ll be at the Dutch House. By using “our father” rather than “my father,” Patchett cues the closeness of this sibling pair and prepares us to enter this so-far-unnamed sister’s perspective. The fact that Sandy tells them, rather than asks them, to come downstairs hints that these siblings are on the young side and also that Sandy has some measure of authority over them.

After this opening paragraph, we continue with the scene Sandy’s dialogue line has activated:

“Is it a work friend?” Maeve asked. She was older and so had a more complex understanding of friendship.

Sandy considered the question. “I’d say not. Where’s your brother?”

“Window seat,” Maeve said.

Sandy had to pull the draperies back to find me. “Why do you have to close the drapes?”

I was reading. “Privacy,” I said, though at eight I had no notion of privacy. I liked the word, and I liked the boxed-in feel the draperies gave when they were closed.

Patchett trickles out a few more details in this exchange: Maeve is the older sibling; our narrator is an eight-year-old boy. Maeve is on the track of the question that most interests us at this stage: Who is Andrea and why is she at their house? Sandy’s considering pause, her use of the anodyne word “friend,” which Southerners of my mother’s generation still use to refer to unmarried romantic partners, only serve to heighten our curiosity. Where is the mother of these two children in the Dutch House? Why does their father want them to meet Andrea? Will Andrea become their stepmother? Maeve, it is hinted, with her “more complex understanding of friendship,” may be alert to this possibility. The purpose of her question is to rule it out.

The last paragraph quoted above gives us our most direct view yet of our narrator, and immediately we are allied with him: like us, he is reading. The “I” in the sentence “I was reading” is the first “I” voiced by the narrator, the first action he relates of himself. Also note the way Patchett is alluding to the opening of Jane Eyre, in which the orphaned Jane is tucked away in a curtained window seat of her aunt’s lavish but lonely house, reading a book, before being violently interrupted by her abusive cousin. The overall message we have received so far is that the Dutch House is not a warm, embracing, nurturing place.

The next paragraph enlarges our view of the house itself, and gives us our first glimpse of the narrator’s father and the mysterious Andrea:

As for the visitor, it was a mystery. Our father didn’t have friends, at least not the kind who came to the house late on a Saturday afternoon. I left my secret spot and went to the top of the stairs to lie down on the rug that covered the landing. I knew from experience I could see into the drawing room by looking between the newel post and first baluster if I was on the floor. There was our father in front of the fireplace with a woman, and from what I could tell they were studying the portraits of Mr. and Mrs. VanHoebeek. I got up and went back to my sister’s room to make my report.

The setting details add to the emerging picture of the formality of the Dutch House: the central staircase, with carved newel posts and balusters; the “drawing room” (not family room or living room), with a fireplace and portraits. The name VanHoebeek gives us a clue about the name of the house and the titles Mr. and Mrs. hint that these portraits are not connected to the narrator and his family. Note too how Patchett embeds some important revelations in what is largely a paragraph full of action summary and setting details: the narrator tells us that his father does not have close friends and reveals that he often spies on whatever might be happening in the drawing room below, when he is not finding safety in his “secret spot” within his older sister’s room.

This takes us through the end of the first page. I’ll speed up now to guide us through the end of the first scene. Patchett quickly gets Maeve and Danny (whose name we learn when his father addresses him) into the drawing room, where we see the mysterious Andrea, still gazing at the VanHoebeek portraits, speak for the first time:

“It must be a comfort, having them with you,” Andrea said to him, not of his children but of his paintings.

Notice how much meaning is layered into that single sentence! Andrea believes (or at least says) that Danny’s father must be in need of comfort (and we wonder again, why?). And she is oriented to believe that physical objects, not human relationships, bring comfort. Or—and this is key—the older Danny that is narrating this remembered scene from his childhood believes he knows this fact about her.

As the scene goes on, the relationships between Danny’s father (whose name is still a mystery, many chapters into the book), Andrea, Danny, and Maeve start to unfold. The father is, as we suspected, cold and distant, giving Danny attention that is too judgmental, and ignoring Maeve altogether as far as possible. Maeve, however, is brave and will not be ignored.

Woven into the scene, which consists of only a brief discussion about the house and its former acreage, is a great deal of backstory, most of it focused on the Dutch House but also sneakily revealing important details about the family: that Danny’s father bought the house and everything in it, including the paintings, after the VanHoebeeks fell on hard times; that Danny and Maeve’s mother has indeed “left,” though we don’t know why; that the father does marry Andrea; that there is long-standing tension between Maeve and Andrea, which some (but not Danny) believe stems from this very first meeting between the two.

Let’s look at two passages that are, ostensibly, setting details but which do far more work for Patchett than just establishing the visuals of the scene. First, we learn more about the portrait we encountered on the cover of the book. It portrays Maeve at the age of ten and was painted by a famous artist brought in from Chicago:

As the story goes, he was supposed to paint our mother, but our mother, who hadn’t been told that the painter was coming to stay in our house for two weeks, refused to sit, and so he painted Maeve instead. When the portrait was finished and framed, my father hung it in the drawing room right across from the VanHoebeeks. Maeve liked to say that was where she learned to stare people down.

Here is a clue to the mother’s absence—and more evidence of the father’s domineering attitude toward his family—as well as insight into the character of Maeve, who refuses to be dominated.

Second, we step back and see the Dutch House from afar:

Seen from certain vantage points of distance, it appeared to float several inches above the hill it sat on. The panes of glass that surrounded the glass front doors were as big as storefront windows and held in place by wrought-iron vines. The windows both took in the sun and reflected it back across the wide lawn.

This description brings us back around to the first meeting of Andrea and the children, which we have moved away from for several pages:

“It’s so much glass,” Andrea said, as if making a calculation to see if the glass could be changed, swapped out for an actual wall. “Don’t you worry about people looking in?”

Not only could you see into the Dutch House, you could see straight through it. The house was shortened in the middle, and the deep foyer led directly into what we called the observatory, which had a wall of windows facing the backyard. From the driveway you could let your eye go up the front steps, across the terrace, through the front doors, across the long marble floor of the foyer, through the observatory, and catch sight of the lilacs waving obliviously in the garden behind the house.

In the scene, this leads to a discussion of money—Maeve’s matter-of-fact, and accurate, answer to Andrea’s question of why the surrounding land, which would have provided the privacy now available only by muffling the grand windows with drapes, was sold off. But one line resonates through the end of the scene: “Not only could you see into the Dutch House, you could see straight through it.” We understand, intuitively, that what Patchett is offering in this novel is a chance to see through this house and its inhabitants as she holds them up for scrutiny, like insect specimens pinned against illuminated glass.

What lessons or strategies can we add to our writer’s toolbox, based on this analysis? Here are just a few:

In your opening paragraphs, think carefully about how your narrator is related to the other people in the scene. How can the names they use—both proper (Mr. and Mrs. VanHoebeek, Andrea) and generic (our father)—subtly convey the status of their relationships or their feelings toward other characters?

Get the most out of your setting details. How can you make them do double duty? Can they evoke a theme of the novel (the glass house)? Can they activate other associations (the Jane Eyre window seat)? Can they suggest backstory (the mother’s refusal to sit for her portrait)?

Use your narrator’s internal reaction to or commentary on a character’s dialogue line to reveal the relationship between them, as in the line about the relative comforts of portraits versus children.

Provide clues for your reader to piece together before confirming them in a way that feels offhand. We suspect Andrea will become the narrator’s stepmother, a fact that is conveyed in a sentence that appears to be descriptive: “at eight I was still comfortably smaller than the woman our father would later marry.”

What lessons or strategies do you notice?